Over the past few months, I have been thinking a lot about workflows to automatically and dynamically improve LLM applications using production data. This stems from our research on validating data quality in LLM pipelines and applications—which is starting to be productionized in both vertical AI applications and LLMOps companies. (I am always very thankful to the teams in industry who find my work useful and are open to collaborating.)

My ideas for data flywheels are grounded in several observations:

- Humans need to be in the loop for evaluation regularly, as human preferences on LLM outputs change over time.

- Fine-tuning models come with significant overhead, and many teams prefer LLM APIs for rapid iteration and simple deployment. LLM APIs do not always listen to instructions in the prompt, especially over large batches of inputs, and there thus needs to be validators on LLM outputs.

- LLM-as-a-judge is increasingly popular. LLMs are getting cheaper, better, and faster.

- Empirical evidence shows that few-shot examples are most effective for improving prompt performance. As such, LLM-as-a-judge can be aligned with human preferences—given the right few-shot examples.

In this post, I’ll outline a three-part framework for approaching this problem. Before we dive into the details of each part, let’s take a look at an overview of the entire LLM application pipeline:

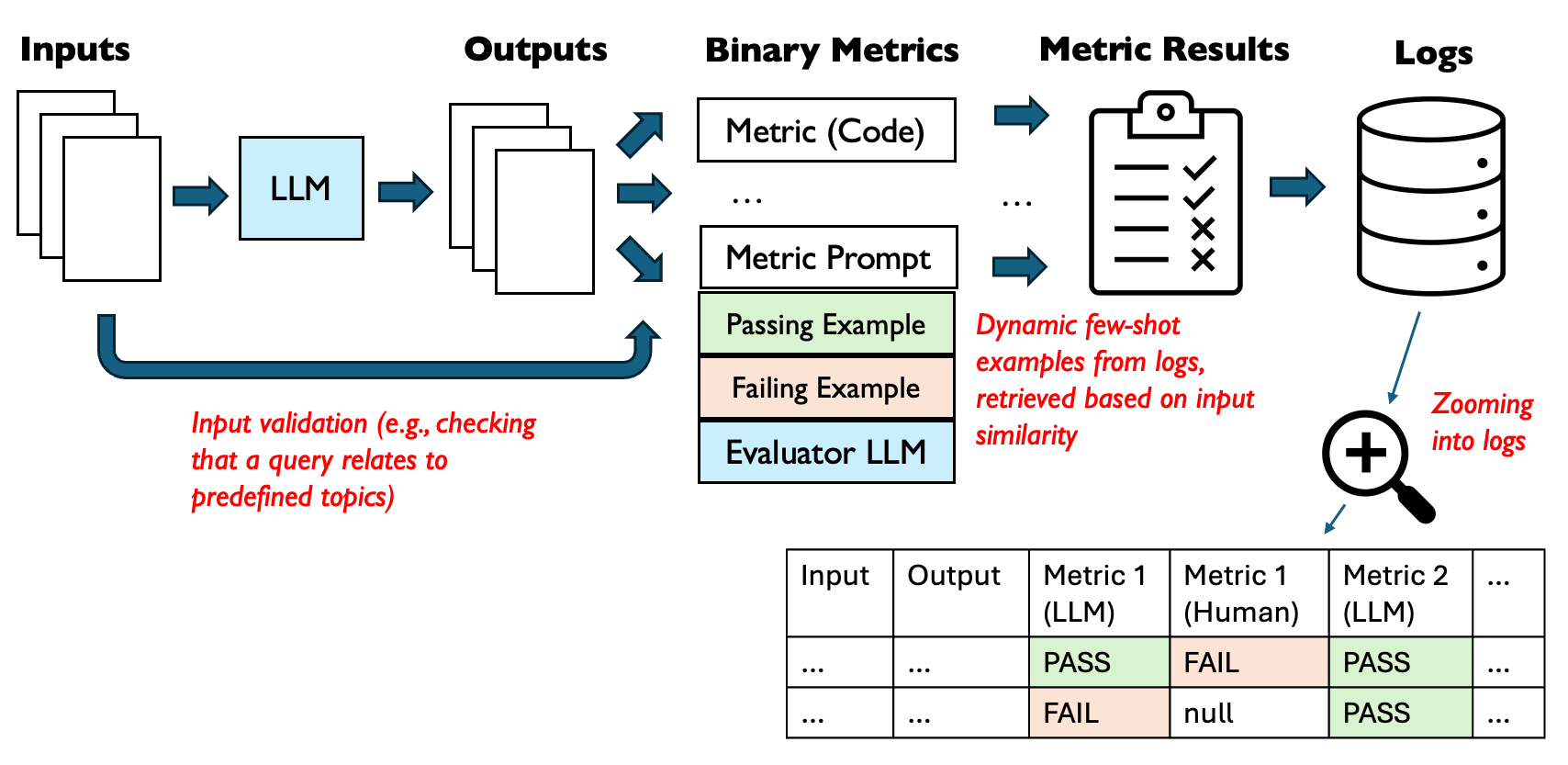

Figure 1: Continually-Evolving LLM Application Pipeline, adapted from the source of Figure 1 in this paper.

This diagram illustrates my (idealized) architecture of an LLM pipeline, from input processing through evaluation and logging. It showcases ideas I’ll discuss throughout the blog post, such as input validation, dynamic few-shot example retrieval, and the use of both code-based and LLM-based metrics for evaluation.

Now, let’s break down this process into the main parts: Evaluation, Monitoring, and Continual Improvement.

A Framework for Creating a Flywheel

1. Evaluation: Defining Success Metrics

There are several great resources specifically on evaluation. Here’s one I really like from my friend Hamel, with concrete examples of what metrics to evaluate and tools to use. I’ll focus on a more high-level overview of the metric process: first, establish clear criteria for success, then, try to find the right implementations of these metrics. This process is more nuanced than it might initially appear:

a) Identify metrics that matter for your specific use case.

For a customer service chatbot, you might care about “response conciseness” or “empathy scores.” However, it’s important to note that you can’t determine effective criteria purely through theorizing about possible failure modes for your task. You need to examine actual data—many LLM outputs—to get a true sense of what criteria you want to validate for LLM outputs for your specific task.

Looking at data to inform your evaluation metrics is necessary because some metrics correspond to LLM idiosyncrasies or even quirks specific to your task. For example, you might notice that words like “delve” and “crucial” commonly give off a “GPT smell” that you want to avoid. In this case, you might implement a metric that checks for the absence of such words. These kinds of insights only emerge from careful examination of real outputs.

Once you’ve identified the right metrics for your use case, the next step is implementing them effectively:

b) Implement these metrics.

As depicted in the “Binary Metrics” section of Figure 1, we can use both code-based metrics and LLM-based metrics (via prompts) for evaluation:

- Simple code functions to assess heuristics: For instance, character counting for conciseness.

- ”LLM-as-a-judge”: Querying an LLM to evaluate a specific metric that you define. This approach is particularly useful for more subjective or complex criteria.

When using LLM-as-a-judge, aligning the judge’s outputs with your own judgment can be challenging, especially for custom or bespoke tasks. Providing some examples of what you think are good and bad LLM outputs (with respect to your metric) in the judge’s prompt can significantly improve alignment.

It’s worth noting that binary metrics (True/False) are much easier to align and reason about from a UX standpoint. Many people reflexively turn to Likert scales or more fine-grained metrics for LLM judges, but it’s often better to start simple. Binary metrics are easier to align (you only need to agree on what constitutes True and False) and easier for humans to consistently judge, which is important for maintaining the quality of your evaluation data over time.

c) Validating multi-step pipelines (i.e., “graphs” of LLM calls).

In complex LLM applications with interconnected “graphs” of LLM calls, we can think of validators as probes in software observability. Just as probes are strategically placed to monitor software behavior, validators should be placed in LLM graphs to assess the quality and correctness of intermediate and final outputs. For each type of node in an LLM graph, we want to probe its behavior differently. My friend Han proposed three node types that resonated with my experience. I found his categorization insightful and decided to expand upon it with my own observations from the field:

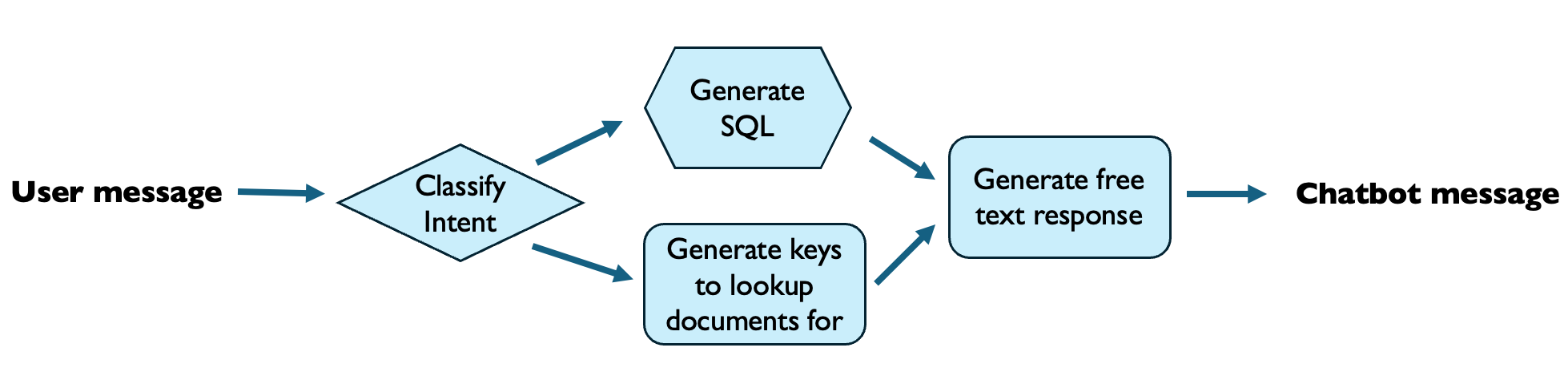

Figure 2: LLM-based nodes in a customer support chatbot pipeline. Diamond nodes represent classifiers, hexagonal nodes represent codegen nodes, and the rectangular nodes represent LLM-as-writers. This diagram omits tool use (e.g., executing the generated SQL statement against a database; looking up keys in a knowledge base to find documents that might answer the user’s query) for clarity.

- LLM as Classifiers (State Transition Nodes; Diamond Nodes in Figure 2):

- Example: In a more complex customer support chatbot, a state transition node could use an LLM to classify user intents (e.g., “billing issue,” “technical support,” “general inquiry”) and route the conversation to the appropriate subgraph based on the predicted intent.

- Focus on assessing the correctness of decision-making—using metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score.

- Apply rule-based validation (e.g., if the user mentions “bill” or “payment,” the expected intent should be “billing issue”, and if the LLM’s predicted intent does not match the expected intent, flag the conversation for human review and potentially update few-shot examples and training data).

- LLM as Writers (Generative Nodes; Rectangular Nodes in Figure 2):

- These metrics will be the most bespoke, as they are highly user-specific and task-specific.

- E.g., assess quality, coherence, and appropriateness of generated content. Can also metrics like perplexity, diversity, and adherence to task-specific constraints—depending on how actionable these are for the business.

- In the customer support chatbot example, one could write an LLM-based validator to check adherence to the brand’s tone and voice guidelines (based on examples of the company branding).

- LLM as Compilers/Code Generators (Codegen Nodes; Hexagonal Nodes in Figure 2):

- Example: In the customer support chatbot, an LLM-as-codegen node could generate SQL queries to retrieve relevant information from a knowledge base based on the user’s intent and context.

- Use static code analysis, linters, and test suites to validate generated code.

- Employ dynamic analysis techniques when applicable, such as automatically executing generated SQL statements against a database in a text-to-SQL LLM pipeline and verifying the output.

- Potentially use an LLM-based validator to determine if the output reasonably answer’s the user’s query.

When implementing validators at every node in the graph of LLM calls, you can easily end up with many validators, and it’s not always clear which ones are most critical. By labeling validator outputs and computing per-step accuracy, you can trace how errors compound across the pipeline, providing valuable insights for targeted improvements. I think that comprehensive solutions for validating multi-step LLM pipelines are still an open research question, which I’ll discuss further later.

d) Validate inputs as well as outputs.

Input validation, illustrated on the left side of Figure 1, ensures that only appropriate queries are processed by the LLM. While the majority of literature focuses on validating LLM outputs, validating input data is also important for building robust LLM applications. This ensures that your pipeline handles only inputs it was designed for, rejecting or flagging out-of-distribution inputs.

While data validation is well-explored for traditional ML, adapting these techniques for bespoke LLM pipelines with free-text inputs often requires equally bespoke validation approaches, in addition to general validation (e.g., language detection).

My general philosophy here mirrors Brendan Dolan-Gavitt’s, who says: “the best design principle seems to be Postel’s Law: be strict in what you send to the LLM, and liberal in what you accept as a valid response.” Let’s consider a customer support chatbot example to illustrate some input validation metrics:

- User Authentication:

- Metric: Query relates only to the authenticated customer’s data

- Implementation: Compare entities mentioned in the query (e.g., order numbers, account details) against the customer’s record in your database

- Topic Relevance:

- Metric: Query relates to predefined support topics

- Implementation: a) Keyword matching: Check for presence of key terms related to your support areas b) Semantic similarity: Calculate cosine similarity between query embedding and embeddings of your support document set, setting a minimum threshold (e.g., 0.7)

- Query Complexity:

- Metric: Query length and structure fall within expected ranges

- Implementation: Set acceptable ranges for token count, sentence count, and presence of specific syntactic structures

- Language Detection:

- Metric: Query is in a supported language, like English

- Implementation: Use a language detection library to ensure the query is in one of your supported languages

- Sensitive Information Detection:

- Metric: Query does not contain unexpected sensitive information

- Implementation: Use regex patterns or named entity recognition to flag potential presence of sensitive data (e.g., credit card numbers, social security numbers)

- Adversarial Input Detection:

- Metric: Query does not attempt to manipulate the system

- Implementation: Check for known adversarial patterns, such as repeated attempts to access other users’ data or prompt injection attempts

- Anomaly Detection:

- Metric: Query is similar to recent queries

- Implementation: Compare the query’s embedding to embeddings of recent queries. If the similarity falls below a threshold, flag it for human review

One can also use LLM-based validators to validate inputs—which also raises the question of how to align the LLM with human judgment. I’ll discuss this in the next subsection.

2. Monitoring: Operationalizing Metric Implementations

Once you’ve defined your metrics, the next challenge is ensuring they keep up with production data. This process should be as automated as possible, given the dynamic nature of LLM applications.

a) Automatically reassess if your chosen metrics still align with your goals.

The metric set that you come up with from the previous section is not meant to be static. When you deploy your application, you will learn of new failure modes, and you may want to update your metric set. Moreover, LLM APIs are constantly changing under the hood, and your ideal system behavior will evolve over time.

One idea to semi-automate the evolution of your metric set is to consider deploying an LLM “agent” that regularly analyzes a sample of labeled production data to determine if your metric set needs updating. This agent could:

- Propose new metrics (e.g., if customers consistently dislike certain phrasings)

- Suggest changes to metric definitions (e.g., realizing that conciseness is more subjective than a simple character count)

- Recommend removing metrics that don’t correlate with key performance indicators like accuracy or click-through rates

In the prompt, the LLM agent only needs samples of the production data and the current metric set. While this LLM agent can automatically run regularly, it’s probably important that an AI engineer actually verifies new metric sets before implementation.1

While an LLM agent can help evolve your metric set over time, it’s equally important to ensure that your metric implementations also evolve.

b) Keep metric implementations aligned with your evaluation criteria.

Alignment has to be continually reassessed as production data drifts over time. This is particularly important for LLM-based metric evaluators. A more detailed workflow might look like this:

- For each metric, regularly sample and label a set of responses from production data.

- Store these labeled examples in a database, preferably with timestamps for recency tracking. I know of some people who also store embedding-based indexes of their labeled examples.

- For code-based metric implementations, schedule periodic manual reviews to ensure the code still captures the essence of the metric given recent data.

- For LLM-based evaluations, keep the validator prompt dynamic:

- Retrieve examples from your database that are relevant to the instance being validated. The dynamic few-shot examples, highlighted in Figure 1, are retrieved based on input similarity.

- Consider an active learning-inspired approach: prioritize retrieving examples where human labels differed from what an LLM would predict. This helps focus on edge cases and areas of potential misalignment. I know of 2 people who do this (TBD on how much lift it provides over uniformly randomly sampling examples.)

- Weight similarity scores by label recency. Recent production data should have a higher likelihood of being selected as few-shot demonstrations compared to older data. Take this specific recency-weighting idea with a grain of salt–I don’t know of anyone who is doing this right now, but it seems important. (Interestingly, I know of one person who retrieves the most recent few-shot examples without looking at semantic similarity—mostly because there is low data volume, so semantic similarity may not help.)

One significant challenge in this process is ensuring regular human labeling of data for each metric. It’s important but can be burdensome. LangChain is exploring an interesting approach to this: using an LLM to label data by default, with humans able to edit these labels as they choose. While this definitely alleviates the labeling burden, it’s unclear how well the LLM labeler will align with human judgment over time–especially if engineers or team members are lazy and don’t want to verify labels. However, even if not perfect, this approach ensures a constant stream of recent, relevant examples for few-shot demonstrations2, which is valuable in and of itself.

3. Continual Improvement: Closing the Loop

With robust evaluation and monitoring in place, the focus shifts to systematically improving your application. This process involves both (manual) human insight and automated techniques to enhance performance based on real-world usage. As illustrated by the “Logs” component in Figure 1, a prerequisite here is to maintain a comprehensive log of outputs and their associated metric scores; many LLMOps tools (e.g., LangSmith) can help with this.

a) Manually iterate on prompts or pipelines to enhance performance on your defined metrics.

The key here is leveraging the insights gained from your evaluation and monitoring processes. With well-defined metrics and continually evolving implementations, you can identify which production traces performed well and which didn’t, and learn from mistakes to improve prompts or other application components.

Some strategies to consider:

- Regularly review the distribution of metric scores across your production data. Look for patterns or clusters of low-performing instances.

- Do analytics on inputs or query data distribution to observe patterns and changes in user behavior.

- Try A/B testing different prompt structures or pipeline configurations to empirically determine which performs better on your metrics.

b) Automatically improve the pipeline in response to metrics.

While human analysis described above is valuable, automating parts of the improvement process might improve efficiency. Here’s what I imagine could be a basic improvement strategy:

- Regularly review and “fix” low-scoring outputs. This can be done on a daily or weekly cadence, depending on your application’s scale and resources. The “fixing” process involves:

- Identifying what went wrong in the original output

- Rewriting the output to be correct

- Documenting the changes made and the reasoning behind them (for other team members to learn from)

- Implement an active learning-inspired approach for continuous improvement:

- Keep a database of production traces along with their metric scores and any human-provided fixes.

- For traces with low scores, prioritize them for manual review and fixing.

- During LLM inference at application runtime, retrieve the most similar “fixed” traces to the current query and include these as few-shot demonstrations in the prompt.3

- You can experiment with different retrieval strategies, such as:

- Including both the most similar trace (regardless of its score or whether it was fixed) and the most similar fixed trace

- Weighting the retrieval by recency to favor more recent examples

- Incorporating a diversity measure to ensure a range of example types in your few-shot demonstrations

It’s worth noting that decomposing “good” outputs into multiple dimensions, rather than just having humans label traces holistically, offers several key benefits:

- Breaking down quality into specific metrics enables more accurate and consistent human labeling. Instead of making a single, high-level judgment, raters can focus on well-defined aspects like conciseness or politeness. This granularity promotes alignment and reduces subjectivity.

- Aligning LLM validators becomes easier when they only need to check a single metric at a time. Trying to capture the full notion of “goodness” in one fell swoop is challenging, but validating individual dimensions is more tractable.

- Having scores for each metric provides a more nuanced view of performance. If most outputs are failing due to a specific metric, it pinpoints the area needing improvement.

So while involving human labeling regardless, using multiple metrics brings rigor, consistency, and actionable insights to the continual improvement process. It allows for a more systematic and effective approach to refining LLM applications over time.

LLM Applications: A New Set of Challenges

The framework I’ve outlined provides a solid foundation for building self-improving LLM applications. However, as we push the boundaries of what’s possible with these systems, new challenges emerge. Here are a couple of problems I’ve been thinking about in the LLMOps lifecycle, more from a research perspective:

Applications of LLM Uncertainty Quantification to Aligning Validators

One key challenge is uncertainty quantification for LLM APIs, especially when dealing with custom tasks. Active learning, a powerful tool for improving ML models, becomes challenging with LLM APIs, where we lack meaningful probability estimates. Next-token probabilities from instruction-tuned models are uncalibrated and unhelpful when analyzing outputs at scale. Some ML research papers explore asking LLMs to simply output confidence scores after their outputs, but this doesn’t work all that well either. Of course, a straightforward solution is to fine-tune LLMs instead of using LLM APIs, but this ignores the premise—the simplicity of LLM APIs.

Robust uncertainty estimates could significantly enhance our ability to align metric implementations, sample informative few-shot examples, and prioritize data for human labeling. While this is an open research question, advances in this area could directly strengthen the Evaluation and Continual Improvement components of our framework.

Data Flywheels for “Graphs” of LLM Calls

As LLM applications grow in complexity, we often deal with interconnected networks or “graphs” of LLM calls, representing multi-step reasoning processes. Some applications even put LLMs in loops! Implementing data flywheels for such systems presents unique challenges:

- Errors from one node can amplify through subsequent nodes, necessitating early detection and correction.

- We need to assess the quality of both intermediate and final outputs. This can be a lot for a human to manually grade.

- Graphs are dynamic: LLM-based graphs might change structure based on inputs or intermediate results, complicating evaluation and improvement processes.

To address these challenges, key research directions include:

a) What does it mean to implement graph-aware evaluation metrics? Do we employ some form of hierarchical validation—where we validate individual LLM calls or nodes, walks or subgraphs, and then entire graphs? These validation probes should probably be different for different types of nodes, but what are the types and how should validation differ?

b) How can we design systems that dynamically insert validation probes at critical junctures in the graph? This approach could involve developing algorithms that identify high-risk nodes or transitions based on historical performance data or uncertainty measurements—or causal analysis techniques. Ideally, we can catch and correct errors early, before they propagate through the system.

c) Can we extend the concept of dynamic few-shot learning to graph structures? This might involve developing techniques to retrieve relevant subgraph traces based on the current graph configuration and task. We could explore using graph-aware embeddings or subgraph matching algorithms to find similar patterns in historical data.

Database-Driven LLM Pipeline Validation

I am curious about integrating validators directly into database systems. Currently, it’s a lot of work for application developers to implement logging and validation of all traces. It’s challenging to implement few-shot retrieval, ensure all validators (especially LLM-powered validators) complete successfully, write the results to the DB, etc., in real-time or even in the application background—especially given that this can require significant computational resources or take a long time to run. Ideally, the database can do this for us.

Key questions I’ve been thinking about include:

a) Implementing validators as database triggers or stored procedures: This allows for automatic execution of both code-based and LLM-based validators whenever new data is inserted or updated. How can we design these triggers to be efficient and not significantly impact database performance?

b) Using database views for flexible metric computation: By implementing metrics as views rather than computing all metrics (which could be costly, especially if LLMs are evaluating metrics), we can potentially save resources. What are the trade-offs between on-demand computation and materialized views for different types of metrics?

c) Incremental maintenance of semantic indexes of logs: For efficient retrieval of few-shot examples, we need to maintain up-to-date semantic similarity indexes for LLM pipeline traces. Are there simple incremental update strategies to keep these indexes current without full rebuilds?

Wrapping Up

Building self-improving LLM applications is about applying a systematic approach, focusing on what truly matters for your use case, and iterating based on real-world performance. The framework I outlined is intentionally simple: it doesn’t rely on sophisticated tools, ML platforms, or enterprise-grade monitoring systems. Instead, it emphasizes thoughtful metric selection, consistent monitoring, and data-driven improvements.

At the end of the day, people (myself included) won’t be happy until all production data is maximally leveraged for future pipeline runs—and this hopefully-simple approach makes a big leap in turning every production trace into an opportunity for refinement and enhancement. Of course, there is still work and research to do—e.g., LLM-as-a-judge is not perfect, and LLM applications can be pretty complex, possibly requiring different validation techniques.

Zooming out a bit—I think it is such an exciting time to be building intelligent software applications. Self-improving applications are actually possible to build right now, and there are still many questions to answer. But I am most excited because the path forward will be collaborative and interdisciplinary—uniting industry practitioners, researchers, and experts across various fields and subareas of computer science—as we chart the future of engineering intelligent software.

Thanks to my friend Han Lee for his valuable feedback and insights on an earlier draft of this post. I also thank my advisor Aditya Parameswaran for suggesting the idea of a detailed blog post on our recent LLMOps research, and my colleague Parth Asawa for inspiring the narrative around the data flywheel concept.

If you are interested in collaborating on any of these research projects, please feel free to reach out to me at shreyashankar@berkeley.edu. Include your CV and specify the project you are interested in, along with any initial thoughts or ideas you might have.

Footnotes

-

While I have not seen any agent that does exactly what I have outlined above, Alta, a startup that I work with, employs an agent to automatically suggest changes to metric definitions. I think Alta’s approach is awesome and allows them to be ultra-personalized (i.e., have a different metric set per end-user), and I am excited to see how it evolves over time. ↩

-

Han raised a good point here while reviewing the blog post: this approach might not be kosher for some industries, e.g., what if the legal team wants to “sign off” on prompts before they go into production? Or, what’s the risk of prompt poisoning here—can someone adversarially write queries that get included in the prompt as few-shot examples? ↩

-

I really like this blog post (authored by my former colleague Devin Stein), which champions dynamically fetching examples for the prompt at runtime. At least 5 people that I know are doing something similar. Interestingly, this architecture shifts the prompt engineering problem to a retrieval problem—how do you retrieve examples that are (1) most informative for the LLM, and (2) most correlated with what the end-user might want? ↩